It is well known that 90% of hardware production/quality issues are related to pasting performance. For those unfamiliar with the topic, pasting is the process of adding a special “solder paste,” basically a mix of tiny micrometer-size metal balls and flux, which can be applied on the PCB using a “stenciling” method.

After adding the paste, you are free to populate all the components (microchips, resistors, capacitors, etc.) to later end inside the reflow oven which melts the “paste”, and solder all the parts onto the circuit board. Easy right? Well, no.

My history of hardware assembly dates back to 2007, when I was starting up 3DR in my garage; our methods were very modest back then. Over time, we gained experience, afforded better equipment, and implemented proper assembly procedures. After 3DR had decided to change its course to software, I then opted to found mRo, which is fundamentally a spin-off the 3DR hardware division. This time I wanted to keep production in California, so I could personally be in front of the manufacturing process and keep control of quality (and why not? Get fun in the process).

Even with all this experience coming from very capable people (that used to work in 3DR), I have to admit that restarting the company was a nightmare! We had so many problems stabilizing the production line, many things failing for no reason and we could not explain why.

When I say “fail”, I’m not implying that our products had bad quality, what I mean is that from 100 units that we built, only ten units were working properly, and this situation made the company unsustainable (and very frustrating).

After a lot of tests and hard work, we increased our yield to 50% and quickly raised it to 70% by adjusting our procedures, implementing repeatability and traceability, and calibrating all our machines; but still, something was missing.

So after pressure from my peers, I decided to buy two (very expensive) and sophisticated pieces of machinery: a Mirtec LV-7 AOI (Automated Optical Inspection machine) and a Kuh Young KY-3020V SPI (Solder Paste Inspection), both South Koreans.

The AOI removes the human variable when you are looking for missing, shifted, lifted components, among other things on your board; but, I will leave this topic for another post. I’m dedicating this one to the Kuh Young SPI.

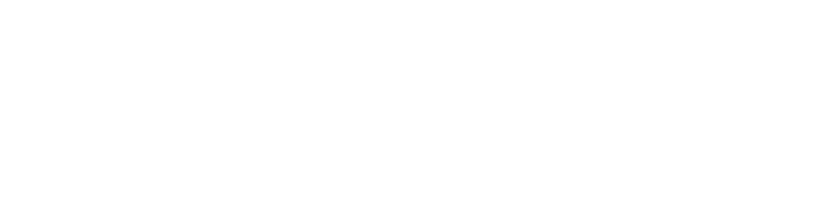

The SPI is a machine very similar to an AOI, which removes the human variable and allows us to see stuff humans can’t see, like calculate volumes and shifted or missing paste.

The SPI was a last-minute purchase after the person who sold me the Mirtec recommended me an SPI so I could increase my quality to near-military standards, so I decided to give it a try!

After receiving them, I could not wait for the training session, so I decided to personally spend some time trying to figure out how it worked, just because I could. As expected, I didn’t go very far, but I was able to create the “pad” files. The pad files are the files needed to tell the machine what paste pads to inspect on the PCB. Those files are generated from the stencil file (gerber) that you normally use to order the circuit board stencil.

After the pad file has been created, you load it into the machine, define the thickness, among other tolerances, and viola! You are ready to start inspecting your paste quality. Bored?

After running a few pasted boards, I was impressed with how capable the machine was. I did simulate some failures by removing solder paste from some of the pads, and the machine was able to pinpoint them with no hesitation.

Most of the time the shape of the paste doesn’t matter, what matters is the volume % or the amount of paste on each pad. If you lack paste, then you might not properly touch the component, or have a weak joint. Too much paste, and you might have a short circuit. Obviously, I’m simplifying things here. There are more variables that have to be considered as well.

After a couple of inspections on complex boards, we realized something was very wrong. It turns out that 30% of our pads lacked paste, which is below 50% of the required volume. And the fun begins when you discover where your problem is.

Interestingly, the smaller pads were the ones missing paste; sounds obvious, but not always is the case. So with this information in hand, it was time to start trying differents approaches to solve the issue.

We began by tweaking our pasting machine; we reduced squeeze speed, we increased the pressure, we super calibrated it, but still, we had a lot of paste missing. The SPI was telling us the smallest pads were not receiving enough paste.

Then, we assumed that maybe the temperature of the paste was to blame, but it was not. Then I proposed two solutions: we either make the stencil holes “bigger” so more paste can get in, or we try to look for paste with less viscosity (if any).

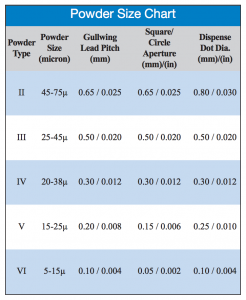

After Googling around, turns out there is solder paste with different “viscosity,” but I was not using the proper term. It is better known as “powder size” and they have levels (T1, T2, up to T6). We were using the T1, which has the biggest powder size (greater than 75 microns). Here you can check size difference:

(Stolen from Nordson EFD)

We tried T4 & T5 and the difference was night and day!

Problem solved! It’s funny, but from all the experienced people I have in-house, no one was in charge of handling the paste back in 3DR (it was another guy). So we had no knowledge of these “tiny” but critical variables (we adhere to IPC standards). Now we do, and you can get very crazy with some math equations to calculate the apertures width of the stencil and compensate for many other variables.

I would never imagine we would learn a lot from this machine; it reminded me of the importance of having the right tools, rather than just keeping an approach of “trial & error.”

Our Kuh Young SPI has initially helped us dominate the basics of pasting. Now, that we have improved and stabilized our processes, the machine will start to fulfill its original purpose – to avoid severe paste issues generated by accidental “fingering”, blocked stencil holes, or simply old, muddy paste (resulting in cost reductions and greater user satisfaction).

I feel lucky I was born in an era where technology has spread successfully to almost all areas you can imagine; from dive computers used to help us avoid decompression sickness to ForeFlight for airplane pilots (which pretty much covers all my hobbies).